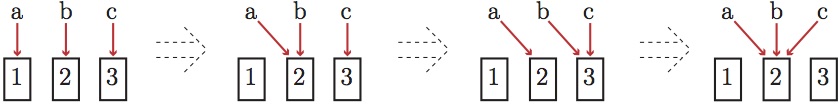

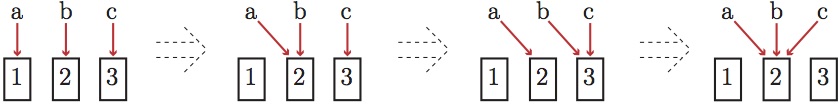

Figure 2: Aliasing of members (letters) to variables (boxes)

Aliases in Cicada are a sort of memory-safe alternative to pointers. An alias is a member that shares its data with some other member: in other words those two members share a variable. In Cicada a member and an alias made to it are exactly on equal footing: the interpreter doesn’t know or care which came first.

Here is how aliases are defined:

a := 2 | will default to an int

b :=@ a | alias #1

c :=@ b | alias #2

‘b’ is now an alias to ‘a’, and ‘c’ is now an alias to ‘b’ and therefore also to ‘a’. If we were to now print(a), print(b) or print(c), we would get back the number 2. If we were to set any of the three variables to a different value:

c = 3

then printing any of a, b or c would then cause the new number 3 to be printed.

Any variable can become an alias for any other variable of the same type (or a derived/inherited type), by means of the equate-at operator ‘=@’.

a :: b :: c :: int

{ a, b, c } = { 1, 2, 3 }

a =@ b | 'a' now points to the variable storing '2'

b =@ c | 'a' STILL points to the variable storing '2'

c =@ b =@ a

The tricky bit is the fourth line: since member ‘a’ has been aliased to member ‘b’, does the command b =@ c now drag member a along with it? The answer is no: aliasing binds one member to another member’s variable, not to the other member itself. If we follow through all the acrobatics, we find that members a, b, and c all end up referring to same the variable storing the number 2, as shown in Figure 2. The other two variables are now permanently inaccessible and will eventually be cleared from memory.

Cicada clearly makes an important distinction between members and variables. A member is a named object in Cicada: the name of a variable, or a field in a composite variable. The variable itself is the data that the member refers to. In Cicada these two objects are entirely separate, and there is no reason to require a one-to-one correspondence between them, as Figure 2 shows.

Just as the data-copying operator ‘=’ or ‘<-’ has a data-comparison counterpart ‘==’, so the reference-copying operator ‘=@’ is mirrored in a reference-comparison operator ‘==@’ which tests to see whether two members point to the same object. (If the left side spans a range of array elements, then the right side must also span exactly those same elements in order for the test to return true). Finally, the are-references-not-equal operator ‘/=@’ is just the logical negation of ‘==@’. Whitespace just before the ‘@’ is allowed:

if a == @b then c := @b

if a /= @b then a = @b

and can help make clearer the analogy with the data-copying operators. Both a = @b and a = b cause member ‘a’ to equal member ‘b’, though by different means.

Jamming

Arrays can also be involved in aliasing. For example, scalar members can alias single array elements, and array members can alias other array members having compatible types.

array_1 :: [5] double

array_2 :: [10] double

oneEl :: double

oneEl = @array_1[4]

oneEl = @array_2[top]

array_1 = @array_2

It gets a little more complicated when aliasing array elements. This is different from aliasing arrays: a1[] = @a2[] is different from a1 = @a2. Cicada doesn’t let us re-alias only part of the source array, since doing so would fragment its storage, but we can alias all source array elements to a part of a target array. For example,

array_1[] = @array_2[<4, 8>]

is legal, as long as array_1 had 5 elements to begin with (aliasing can’t resize an array). However, we cannot write

array_1[<3, 5>] = @array_2[<4, 6>]

There’s an additional complication: what happens if we try to resize one of those two arrays? That could force a resize of another alias, which is not allowed. The solution is that parts of an array having multiple members pointing to them can become ‘jammed’, meaning that they cannot be resized until all but one of the aliases is removed. For example:

array_1 :: [3][10] int

array_2 := @array_1[2][<4, 7>] | jams 4 indices of array_1

array_1[][^12] | legal - indices 11-12 aren't aliased by array_2

array_2[^12] | no, this would cause problems

remove array_1[][5] | not legal -- would remove 2nd column of array_2

remove array_1[1] | legal

remove array_1

array_2[+3] | legal only because we removed the jamb

Explicit aliases always jam arrays. On the other hand, ‘tokens’ or unnamed references to objects (such as elements of sets and function arguments) never jam arrays.

al := @my_array[<4, 6>] | jams elements 4-6

my_array[<4, 6>] | does not jam

Tokens are ‘unjammable’, both in the sense that they cannot jam, and that they will become ‘unjammed’---i.e. permanently deactivated---if their referent is resized through another member. An unjammed token becomes unusable until it is redefined, usually when the command defining the token is rerun.

Last update: November 12, 2025