Cicada ---> Online Help Docs ---> Cicada scripting ---> Functions

Search Paths

A Cicada function has access not only to its own members, but also to members defined at the global level (the workspace). More generally, the function can access any members along its search path, which goes through any object that encloses the function. We’ll show this with some examples:

allFunctions :: {

...

stringFunctions :: { ... }

numericFunctions :: {

...

theNumber :: double

raiseToPower :: { ; theNumber := args[1], return theNumber^power }

} }

raiseToPowerAlias := @allFunctions.numericFunctions.raiseToPower

allFunctions.numericFunctions.calcLog :: { ; theNumber = args[1], return log(theNumber) }

powerOfThree :: { power := 3 }

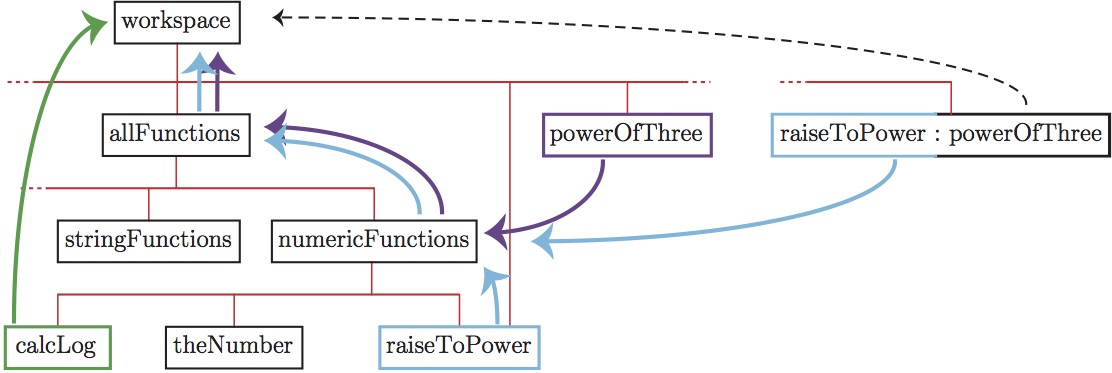

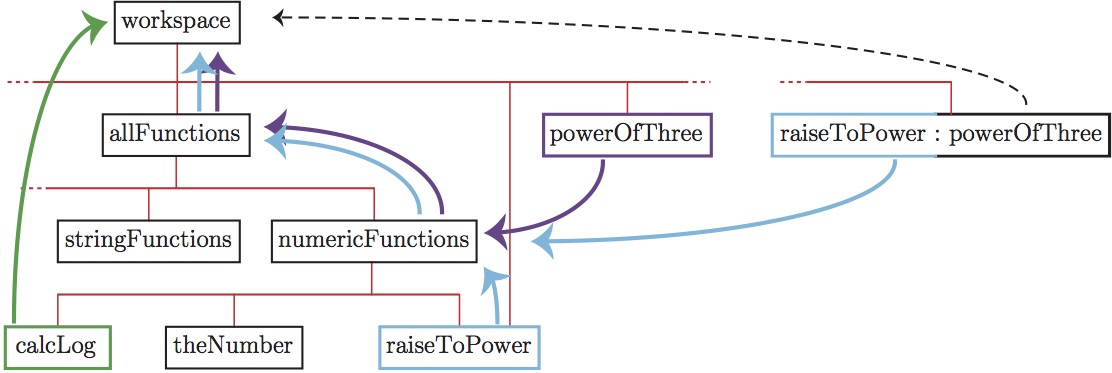

Compare the various functions. The raiseToPower() function has a long but straightforward search path, beginning at raiseToPower, then passing through numericFunctions and allFunctions and ending at the workspace variable (blue path, Figure 3). This means that when its code references a member, it looks first in its own space for that member, then if it’s not there it backs out to numericFunctions and look there; etc. all the way to the workspace if necessary. If it doesn’t find the member by the end of its search path it will crash with a member-not-found error. This search path is used regardless of whether we called raiseToPower() or raiseToPowerAlias() -- it’s a property of the function, not the member.

On the other hand, calcLog()’s search path only touches calcLog itself and the workspace variable (the green path in Figure 3). The reason is that calcLog was defined straight from the workspace, not from the code that defined allFunctions or numericFunctions. So calcLog() cannot find theNumber: it is a broken function. It’s not that the data is inaccessible, it’s that we just need to walk the function to where the data lives. We should have written:

allFunctions.numericFunctions.calcLog :: {

code

theNumber = args[1]

return log(allFunctions.numericFunctions.theNumber) }

Everyone’s door is unlocked, but you have to deliberately open the door to go into someone else’s data space.

Figure 3: Search paths of various functions from an example in the text. For simplicity we’ve named each variable/function box by the member that defined it. Search paths are shown with heavy arrows: green arrows for

calcLog(); light blue arrows for

raiseToPower(); and purple arrows for

raiseToPower() function

substituted into powerOfThree(). A hypothetical function derived from

raiseToPower() and specialized by

powerOfThree() (using the inheritance operator) would have each half its code follow its respective original search path (blue and dotted black arrows from the box at right).

The define operator is special in that it always defines the member right in the first variable of the search path. So theNumber will be defined inside raiseToPower even if there is another member called theNumber further up the search path.

The notion of a search path gives a more accurate picture of code substitution: that operation just changes the first step on the search path of the substituted code. Suppose we write

(powerOfThree << allFunctions.numericFunctions.raiseToPower)(2)

Then the search path for the substituted function begins at powerOfThree but then passes on to numericFunctions, allFunctions, and the workspace variable just as before. This is the purple path in Figure 3. Of course the substitution is temporary, but when the substituted function is run it has a permanent effect on powerOfThree: it creates a member inside of it called theNumber. That member will inherit the spliced search path of the substituted code.

Last update: November 12, 2025